Aboriginal communities have long called for research methods that embrace Aboriginal leadership and challenge traditional researcher-driven approaches. These co-creative partnerships can take time to get right, but a new paper published by Simone Sherriff, PhD student and Project Officer with the Sax Institute’s SEARCH Program, is proving that co-creation in Aboriginal health research is not only achievable, it also leads to more relevant research and better health outcomes.

Co-creation in action

The paper focusses on the real-world case study of SEARCH – the Study of Environment on Aboriginal Resilience and Child Health – which is Australia’s largest long-term study of the health and wellbeing of urban Aboriginal Children.

For over ten years, Aboriginal communities have been driving a research partnership with the Sax Institute that tracks the health patterns of over 1,600 Aboriginal children, identifying gaps in current services, and contributing to additional services such as hearing and speech development. So how and why does this co-creative partnership work?

To find out, Simone, a Wotjobaluk woman whose people are from the Wimmera region in Victoria, and her team spoke to 26 SEARCH stakeholders, including Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal researchers, Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service staff, clinicians and policy partners. They found that co-creating research with Aboriginal communities within an active long-term partnership had built trust and shifted the power axis from the researchers to the communities themselves.

“In the past, researchers came into Aboriginal communities and did whatever they wanted, with little regard for the community,” says Simone. “SEARCH was developed by Aboriginal communities in partnership with researchers, and that sharing of power is unique. I think communities are now in a position of power to say: if you want to work with us, this is how it’s going to be.”

What success (really) looks like

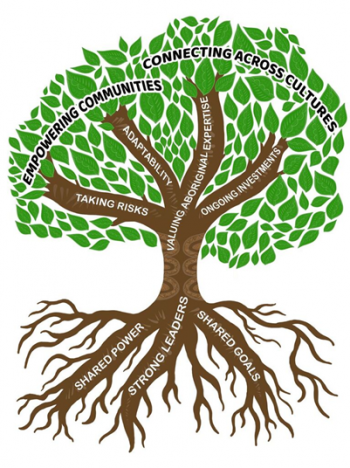

Through this research, Simone and her co-authors unearthed nine steps that they believe are critical to successful Aboriginal health research. These include: shared power; strong credible leadership; shared vision and goals; willingness to take risks; connecting across cultures; empowering the community; and ongoing investment and collaboration. Valuing local Aboriginal knowledge was also a standout theme that Simone says has been historically undervalued.

“Often researchers think it’s enough if there’s an Aboriginal person involved in the project,” explains Simone. “But it’s not enough to have any Aboriginal person – you need the local Aboriginal community involved. Aboriginal community members in SEARCH said they felt they were a valued partner in this project, not just a tokenistic partner.”

Simone also highlighted the need for researchers to stay open to change, as Aboriginal communities have shared experiences but are also uniquely different. “One of the key findings was that you have to be flexible and adaptable. For example, within SEARCH, there are four partner Aboriginal communities and they’re all quite different to one another. SEARCH had to be flexible and adaptable to each of these community’s needs.”

The flow-on effect of this community-led research has also helped ease local fears about research in general.

“People spoke about how it was a big risk for communities to be involved in a research project,” says Simone. “It was quite a leap of faith for them to participate in SEARCH. However, they spoke about how SEARCH has helped demystify research and empowered the community to know what good research looks like.”

Acknowledging the past to reshape the future

Building these kinds of trusting relationships takes time, but it also requires compassion on behalf of researchers. By acknowledging the “terrible history” of Aboriginal health research in Australia, Simone says SEARCH researchers were able to better understand the mistrust felt by Aboriginal communities, and also open up the conversation for what communities wanted to get out of new research.

This is something she hopes all researchers can take on board when working with partner communities. “Aboriginal communities don’t do research to get their name on research papers and PhDs,” says Simone. “They want to be involved in something that is going to lead to positive outcomes for their community, such as funding for new programs, and information to extend current programs and inform the development of relevant policies.”

Which is exactly what SEARCH is doing. Now entering its third phase, SEARCH is using carefully-collected data to inform and support the communities to drive positive changes. Sax Institute CEO, Professor Sally Redman, says this is testament to the transformative effect of collaborative research.

“Working together with Aboriginal communities ultimately leads to smarter research that can make a bigger impact on the health system,” says Professor Redman. “With over ten years of experience behind it now, SEARCH is living proof that co-creation is one research approach that’s worth getting right.”

Find out more about SEARCH here.